Written by Suraj Shah. Inspired by greatness.

As I spend more and more time as a bereavement support visitor, helping those who have lost a loved one to get through their suffering, I would have thought that I’d be pretty good at loosening my own emotional grip on the people I care about.

Yet, as time goes on, I seem to feel more and more heartache at the thought that those closest to me will inevitably one day be no more – in particular, my kid bro.

Sometimes I envision how I might receive the news about his death, or react to finding out about him being hurt in some serious way.

I imagine myself frozen in time, initially standing like a stone cold statue, riddled with shock, and then the next moment collapsing to the floor overcome with the pain of my insides being crushed by the grip of my very own hands.

The grip of my attachement. The pain of my loss.

Nobody is for anybody

In the timeless Jain tradition, there is a reflection titled “anyatva bhavana” which (in Gujarati) states:

“Aa sansaar ma koi koinu nathi.”

This roughly translates to:

“In this worldly life, no-one is anyone’s.”

So why do we feel such strong attachments to our younger siblings, and how can the “anyatva bhavana” reflection help us reduce the torment we relentlessly place on ourselves?

This perplexing attachment toward our siblings

The feeling we have towards our younger siblings, particularly when we grow up after all those initial years of teasing and squabbling, is of care and concern for them, blended with pride of what they have achieved in life so far.

When I look at my brother (he turned thirty this week), I see a confident caring man who has the company of a loving wife, a stable roof over his head, doing work he is committed to and the loyalty of friendships he has been growing and strengthening since childhood.

However, beneath his confident and joyful exterior, I notice his fears and his concerns. Somehow, I can feel his deepest pains that he appears to cover up. The same pains and doubts and fears that we all have – each and every one of us.

The daily discomforts of our body. The financial constraints of hectic western life. The busy-ness and habits of a time-poor society gradually creeping in.

So yes, I notice his incredible strengths, and I notice the depths of his hurt caused by the strain on a typically fractured worldly life.

It makes me want to hold him high above my head and boast about him to the world, while embracing him with a tight grip, to let him know that everything will be ok.

This is my attachment to my kid bro. The very same attachment you may also be having to those you adore.

Understanding that nobody is for anybody

In this world we realise that nomatter how much we try to help take away someone’s suffering or ask others to reduce our pain, we are ultimately truly alone.

If I am deep in debt and someone hands me a bundle of cash, that may temporarily alleviate my financial problems, but it will not cure me of the greed that led me to that state.

That greed is my own that I need to work on and resolve, so that it need not trouble me forever more.

Whatever we currently experience is a result of our past actions. All the trouble, torment and harm we have caused to others in our past has resulted in troublesome situations for us right here, right now.

Someone may run a red light and crash into the back of the car, or your house may get burned down, or business become bankrupt, or get kicked out of your job, or racially abused or anything else under the sun that causes pain, suffering, disease, despair.

But it needn’t cause pain, suffering, disease or despair.

No-one, nomatter how much they may love and care for us, can truly take that situation away from us. We have to endure it ourselves, witness it, and calmly let it pass.

If we don’t stay calm and let it pass, then what will happen? We get consumed by it, wishing that we didn’t have to deal with it, fighting to shift it from our lives, indulging in anger and causing more harm. This inevitably leads to more trouble for us in the future.

What you do now massively impacts the situations that arise for you at a later point in time.

Guaranteed.

So we must understand that everything happening to us right now is completely our own doing, our fault, our responsibility.

It doesn’t mean sit back and do nothing – we need to deal with the situation appropriately.

But while dealing with it, remain calm and let the matter gradually pass.

No-one can truly take away our pain, nor can we truly alleviate anyone’s suffering.

However, our compassionate hearts give us an opportunity to reach out to another.

When you see someone suffering, you can help them out practically and emotionally, all the while knowing that in all honesty, the only true beneficiary… is you.

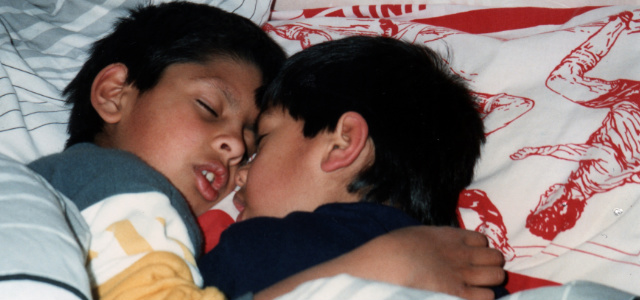

(picture: Suraj with his younger brother Sawan when they were kids)